Differences between haemodynamics of planned and spontaneous speech in people who stutter (PWS)

— By Liam Barrett

We have received a new update from Liam Barrett, one of the Win a Brite winners, whose research focus is on using biofeedback and fNIRS to promote fluency in people who stutter. In this blog post, he shares his findings about the hemodynamics differences in planned & spontaneous speech between fluent speakers and stuttering people.

If you haven’t followed Liam’s research, start with his research here.

We are investigating the neural underpinnings of somatosensory feedback (in the form of vibrotactile simulation (VTS)) in spontaneous (monologue), and planned speech (reading), tasks using the Brite MKII mobile fNIRS device from Artinis. Comparisons are made between PWS and Fluent Speakers.

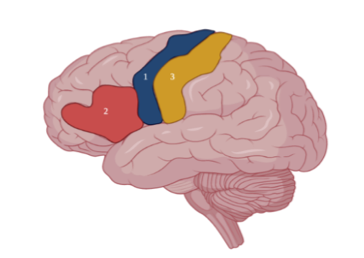

The three regions of interest (ROIs) are:

pre-central gyrus (primary motor cortex, PMC);

Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus (l-IFG); and

the post-central gyrus (Somatosensory Cortex).

Participants performed the monologue and reading tasks with VTS On and with VTS Off.

Figure 1. Left-sagittal view of the human brain with the ROIs indicated. (1) pre-central gyrus, (2) Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus and, (3) the post-central gyrus.

It was expected both frontal regions (l-IFG and PMC) would show significant differences in oxy-hemoglobin in speech tasks. For fluent speakers, the results showed a statistically significant difference in oxy-hemoglobin for both Monologue and Reading conditions only within the l-IFG (top of Figure 2). The PWS group had reduced differences between oxy-hemoglobin and deoxy-hemoglobin in both tasks and the difference was only significant for the reading task (bottom of Figure 2).

The results for the control group were in line with the assumption that the Motor Cortex and left Inferior Frontal Gyrus are involved with planning and execution of speech and language. However, the PWS group data only showed evidence in favor of these regions being involved with planning and execution of speech for the Reading task. This could be attributed to a reduced activation in the execution stage of speech production, perhaps leading to an increased risk of faulty speech-motor execution i.e., stuttering.

Figure 2. Haemodynamic response in left inferior frontal gyral area over 15 seconds. Split by Task (Monologue & Reading) and Speaker (Control & PWS). Note, all responses are significantly greater (p < .05) than baseline (-5:0 Secs) except the response in the monologue task by PWS (bottom-left).

As VTS has a fluency enhancing effect, it was expected that the blood oxygenation levels would increase in PWS in the l-IFG and PMC in speech tasks with VTS when compared to without VTS. So far, with a limited number of PWS tested, there is no significant evidence for this (p > .05). Further testing is required to determine how VTS’s fluency-enhancing effect in PWS is mediated, specifically whether it leads to an increase in neural processing the l-IFG and PMC.

“Work performed by L. Barrett, P. Venkatesh &, P. Howell.”

In hyperscanning, brain activity and connectivity of multiple subjects are measured simultaneously during social interaction, for instance in competitive situations. fNIRS is often used as neuroimaging technology for hyperscanning in cognitive studies due to its portability and relative insensitivity to movement artifacts. In an internal mini-study, we tested the use of Brite Frontal to perform hyperscanning while participants played a competitive game of checker.